25 Jun 2021 Assessing the Racial Cost of Regulation, by Derrick Hollie

If the predictions of the environmental “experts” and their models over the course of my life were true, I’d already be dead.

Born in the late 1960s, I persevered through threats of famine, drought, a diminishing ozone layer, acid rain, killer bees, a new ice age, global warming and more. Each time, the experts were wrong.

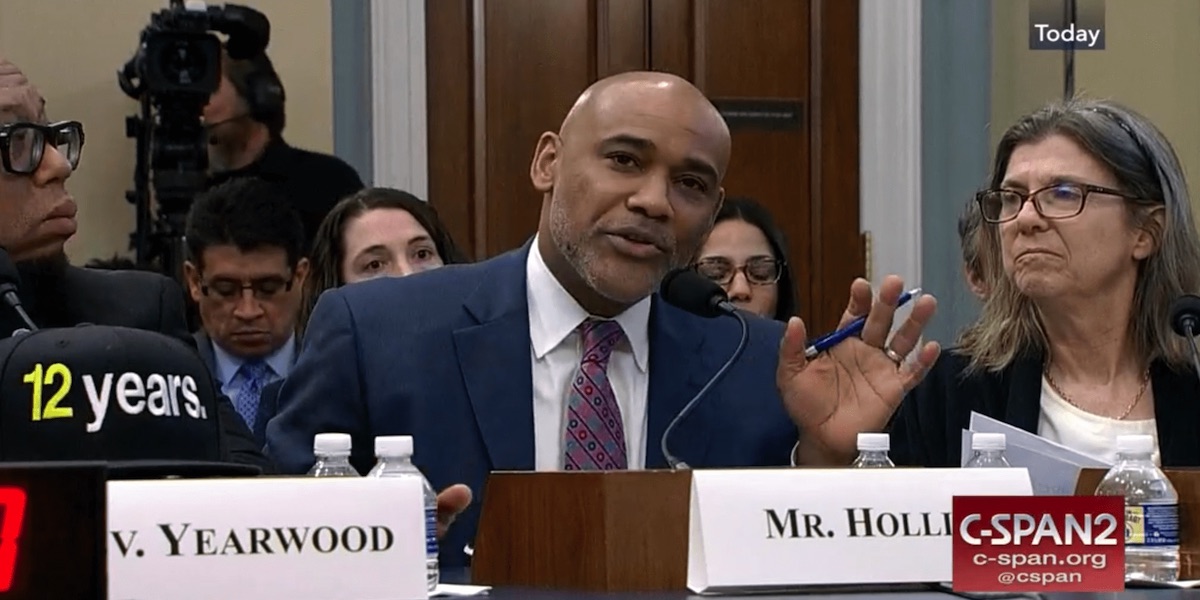

In 2019, I testified at a House Natural Resources Committee hearing convened to discuss the “need to act” about climate change. The man sitting next to me wore a hat emblazoned with “12 years.” It signified the time he and other Green New Deal proponents claimed was left to enact sweeping regulations and avert a climate apocalypse.

Here we are – two years later – and the 2030 doomsday deadline is pushed back another five years.

The hyperbole of a Hollywood-style, world-ending event if I continue to drive an SUV or eat meat is wearing thin, and policymakers know it. That’s why the Biden Administration revived a low-key approach of seeking new regulation based on the “social cost” of greenhouse gas emissions.

An interagency working group, established by one of the president’s numerous executive orders, wants a price tag for “the monetized impact to society” of climate change. Noting the assertion that an “assessment of the positive and negative impacts that an action can be expected to have on society is a core tenet of the policy-making process,” here’s a suggestion: make sure regulations designed to combat climate change – or any regulation, for that matter – have their impact assessed before they’re unleashed on our communities.

That’s why, at that 2019 hearing, I testified about a recommendation from the Project 21 black leadership network to create a “minority impact assessment” for proposed regulations. If this new Biden initiative is true to its claims, this check on regulation must be an integral part of assessing the social costs of climate change policy:

A minority impact assessment would create a list of all the positive and negative impacts a proposed regulation would have on factors including employment, wages, consumer prices and homeownership. This regulatory impact would then be analyzed for its effect on minorities in contrast to the general population.

This deals with the here and now.

During the Obama Administration, a similar executive order produced a similar group that created a similar report that looked hundreds of years into the future for social impacts of carbon helping guide regulations created between 2010 and 2016. A minority impact assessment ensures that new regulations are checked first to find how they would affect Black and Brown communities trying to make their way up the socioeconomic ladder and are most likely to bear the costs and burdens of new federal rules.

This assesses the social costs of climate policy in 2021 rather than 2300. This is a more realistic policy considering the long-term approach is based on models and cannot legitimately factor in what new technologies may be available next year, ten years from now or 100 years from now constituting a complete game-changer in the energy and manufacturing sectors.

A minority impact assessment looks at how regulations affect real people living in real communities right now.

This is a popular idea with those most affected by regulation. An April 2021 poll conducted by tippinsights for Reaching America – a group of which I am president – found that 72 percent of those polled support an assessment of the economic impact of regulations before they are enacted. Broken down, 75 percent of professed liberals living in low-income communities supported it.

People enjoy a clean environment. Americans have done their part to be more responsible. Unlike famine and encroaching glaciers, I watched people voluntarily strive for better communities over my lifetime. But I’ve also seen many struggle with issues like lack of jobs, energy poverty and lost opportunities.

Keeping regulations from taking away opportunity and squashing prosperity – particularly in at-risk minority areas – should be a priority for the White House when looking at the social costs of its environmental policies.

Project 21 member Derrick Hollie is president of Reaching America, an organization that addresses complex social issues impacting African-American communities. This was originally published by Townhall.com.

New Visions Commentaries reflect the views of their author, and not necessarily those of Project 21, other Project 21 members, or the National Center for Public Policy Research, its board or staff.