06 May 2023 Scott Shepard: It’s Congress’s Turn to Address Chase’s Discriminatory Banking Practices

Chase Bank (of JP Morgan Chase) discriminates on the basis of religion and viewpoint, and then lies and lies and lies about it. Nineteen state attorneys general have demanded that the company knock it off. Given that JP Morgan – already too-big-to-fail – just in effect colluded with the Fed and the Treasury to become even bigger, this seems like it would be a good idea. It might also be a good idea if the House Financial Services Committee were to inquire into Chase’s misdeeds.

You’re forgiven for thinking that the next attorney-general interest in Chase would have had something to do with the growing scandal about Chase’s post-conviction support for and interactions with noted-pedophile and unlikely suicide (a phrase that is amenable to more than one interpretation) Jeffrey Epstein. It appears increasingly possible that former executives at Chase may have helped him to hide transactions related to his execratory activities, and CEO Jamie Dimon will be required to give a deposition in the case.

Instead, though, the AGs were focused on conduct that is perhaps less stomach-turning but likely to have vastly wider consequences if not constrained.

Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron’s letter on behalf of the coalition of AGs added some additional information to the controversy that has erupted in the wake of Chase’s debanking of Senator Brownback’s National Committee for Religious Freedom (NCRF) (previously reported about on these pages here).

Chase closed NCRF’s account three weeks after it was opened, initially without explanation. When representatives of NCRF asked about this astonishing development, a number of Chase employees said that the decision had come from the corporate office, and that they “were not permitted to provide any further clarifying information to the customer.”

From the very first, then, we have both Chase executive involvement and stonewalling. Unless, that is, anyone in the corporate offices can close accounts at their unfettered whim and refuse to give any reasons for their actions. Which of these options is correct is a question to which the House committee might address itself.

NCRF’s concern must have trickled back up through the seniority chain, because eventually Chase contacted NCRF to let it know that the bank would deign to restore the account, but only if NCRF provided the bank with a list of its donors, a list of political candidates NCRF intended to support and the criteria it used to make such determinations.

As the internet says: THIS↑. Could there be a clearer demonstration that the executive offices of JP Morgan Chase directly discriminate on the basis of viewpoint, even when that discrimination directly inculpates discrimination on the basis of constitutionally protected religious activity? Or maybe, of course, Chase shuts all non-profit accounts, and then allows them to be reopened once they share this information with Chase. Which one are you betting on? Wouldn’t it be useful if the House committee were to probe that question? To learn how many organizations Chase has pulled this maneuver on, the ideological predispositions of those organizations, and what the results were?

I have a pretty good guess what that inquiry would find. Don’t you?

Chase’s response, when pushed on its insane request, was to continue to lie and lie, citing clearly inapplicable banking regulations to justify its debanking decision – going so far as to cite a regulation that the Fed, the U.S. Treasury and a bevy of other administrative offices had signed onto an explanatory letter about, saying that the regulation did not apply in exactly this situation. But when presented with that fact, the bank clammed back up entirely.

The House committee might ask Chase’s executives in minute detail about their whole series of lies, and drill down to get the truth. Then it could ask them to explain why an entity that discriminates on the basis of viewpoint should enjoy the too-big-to-fail protections it does – at cost to all taxpayers of all viewpoints – and why it should not be forced to disgorge all the profits arising from its takeover this past weekend of First Republic Bank; discriminatory companies have no business colluding with executive agencies to gain not only profits but even greater control of American capital sources.

The committee could pull in the collusive administrative officials at the Fed, Treasury and elsewhere to explain why they’re assisting this grossly discriminatory company to acquire additional assets. U.S. public officials have the duty not to aid and abet discrimination, after all.

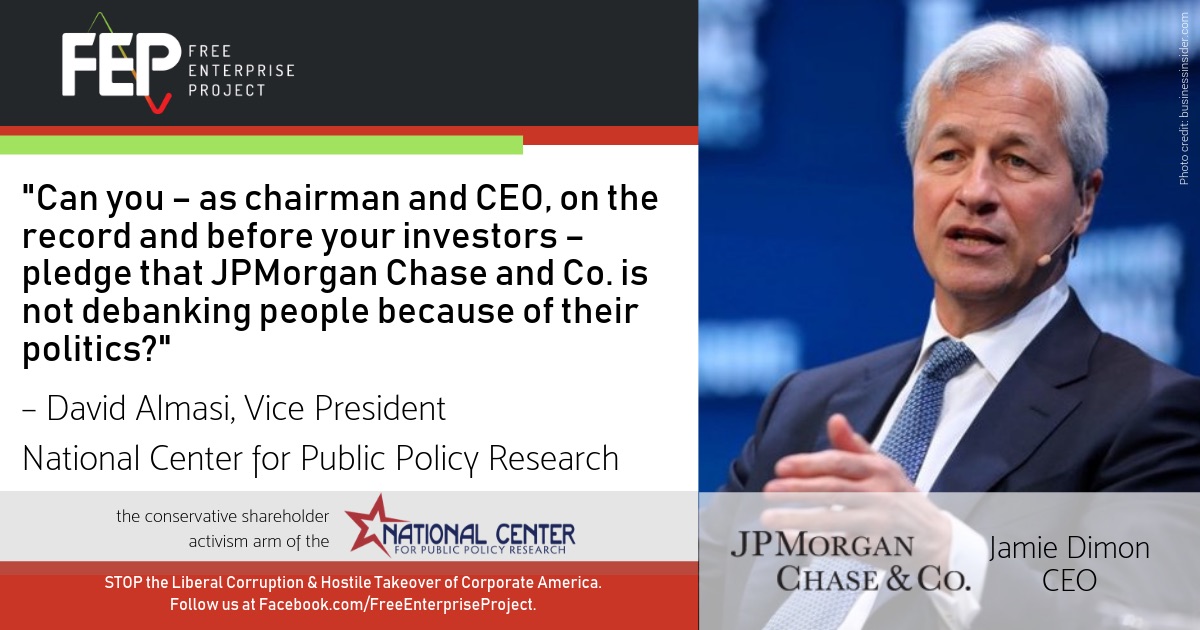

It should also call in Gary Gensler and his chief assistants at the SEC. Attorney General Cameron was kind enough in his letter to point out that the organization I direct, the Free Enterprise Project of the National Center for Public Policy Research, had submitted a shareholder proposal to Chase to challenge its discriminatory policies, only to have the SEC permit Chase to reject the proposal on the ground that this kind of blatant discrimination merely constitutes the “ordinary business” of the company. That’s standard practice at the SEC, where, for instance, efforts to make companies discriminate more in the name of equity or “stopping hate” – such as conservative policy positions – constitutes matters of significant public policy concern that must be included on proxy ballots, while efforts like ours to stop similar discrimination against the right is just ordinary business that companies can exclude.

Last week an amazing team of lawyers at Boyden Gray & Associates filed suit on behalf of the Free Enterprise Project against the SEC for these discriminatory administrative procedures, which among other things violate the First Amendment. (More on the lawsuit as soon as possible.) But it would be great if the House could call Gensler & Co. to testify about this discriminatory treatment. That would shed first light on their excuses, since the SEC’s practice is only to permit or exclude shareholder proposals, never to explain its decisions, while Gensler’s office has refused to allow the Commission itself to review any of the discriminatory rulings.

Wait – do you see some similarity in Chase’s discriminatory modus operandi and that of the SEC? Good heavens. What a coincidence. It’s almost as though the administrative state and giant corporations are colluding to discriminate in favor of hard-left policy goals in violation of law.

If the House committee does call in Gensler and his team, I hope it’ll ask them a question just for me: Just how many attorneys general must weigh in on an issue before it constitutes a matter of “significant social policy concern?”

And one for Jamie Dimon: Care to explain why Chase can’t do business with a religious-liberty organization, but carrying forward with Jeffrey Epstein after his pedophilia conviction was a-Ok?