25 Jul 2023 Melissa Ortiz: One Flag Can Celebrate Two Things, Can’t It?

This photo of the Universal Access Flag Lap Blanket is owned by the National Museum of American History.

July is Disability Pride Month, a 31-day observance culminating with the National Council on Independent Living’s week-long annual conference that concludes with a march to the Capitol and Rally on July 26th – the anniversary of the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

This month-long event is far removed from the earlier days of the fight for full civil rights for disabled Americans. In March of 1990, a courageous group of disabled men and women crawled up the steps of the U.S. Capitol to highlight obstacles faced by people with disabilities. Their objective was to encourage the swift passage and signing of the ADA into law as it was stalling in the halls of Congress.

While others watched them ascend the steps in any way they possibly could, an interesting adaptation of the American flag made its appearance in the crowd. It looked like the American flag with 13 red and white stripes and a field of blue in the upper left corner. But the stars were rearranged into the shape of a wheelchair – the universally accepted symbol for disability access. It was a great testament to the unity and patriotism of those hearty Americans living with disabilities.

It was also a poignant reminder of what was at stake: an accessible environment for all Americans, regardless of ability. For some it was as simple as accessible stores allowing them to do their own shopping. Accessibility also meant enjoying a theatre performance with sign language interpretation for the deaf or hard of hearing. For others, it meant that lowered counters, automatic doors, and braille signage would allow them to conduct banking and other personal business in the same way that an able-bodied American does.

The joy on the activists’ faces when they reached the top of the Capitol steps that day was palpable. So was the immense feeling of gratitude and excitement felt by Americans with disabilities and their advocates when President George H.W. Bush signed the ADA into law four months later. There was a sense of pride in being finally accommodated as fully American alongside their non-disabled fellow citizens.

However, “pride” is a term thrown about with great regularity and carelessness lately. Upon googling it, a popular definition is “a sense of one’s own dignity.” I can appreciate the idea of “disability pride” in that sense, rather than chaffing against it. It is quite different than being puffed up with a sense of self-importance that Proverbs warns us comes before a fall and is recognized as one of the Seven Deadly Sins.

Eleanor Roosevelt said that no one can make you feel inferior without your consent. The assent of those brave folks up the Capitol steps was their statement to the world that they refused to continue to be made to feel inferior. Every person is worthy of being treated with dignity, regardless of their lack of physical or mental abilities. When we have a true sense of our own dignity and worth, we tend to carry ourselves in such a way as to elicit dignified treatment. We choose not to allow ourselves to be made to feel inferior.

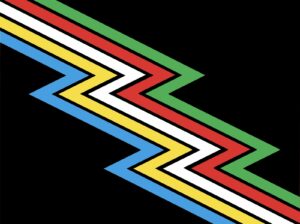

Disability Pride Flag, designed by Ann Magill

The flag embraced by the disability community has changed. It bears no resemblance to the American flag and has no wheelchair on it. It’s multicolored, and one must research its meaning to understand what it represents. It also has nothing to do with identifying as an American who happens to have a disability the way the original flag did. Its very design is indicative of the “pride” bandwagon that has been making its way through society as of late with various iterations of the rainbow flag adopted by the LGBTQ+ crowd – and could indeed easily be mistaken for just another iteration of that one.

What started out as a clear and patriotic representation of Americans with disabilities has morphed into a hot mess of symbology. The new disability pride flag, first unveiled in 2019, was updated in 2021 to a five-color rainbow-esque swath on a black background. This is being driven by a woke ideology incessantly pushing for intersectionality across the civil rights movement which includes people with disabilities and embraces globalism over American patriotism.

Ironically, the designation of disability was overlooked in the original definition of intersectionality that was first coined by critical race theory pioneer Kimberle Crenshaw. She began using the term to represent the overlap of social group designations that include gender, race and socioeconomic status in systems thought to originate in oppression – dividing us under the auspice of uniting us.

For a month devoted to celebrating the passage of the ADA — the first law of its kind in the Western World — that also encompasses the anniversary of the founding of our Republic, it seems rather odd to celebrate it with a flag that does not even hold a glancing resemblance to the original Stars and Stripes.

Being an American is something to appreciate and honor. While a disability is nothing to be hidden, or a source of shame, it should also not be used as a tool to promote divisive pride. If we must have a flag, have one that celebrates our unity.

Melissa Ortiz serves the National Center for Public Policy Research as the organization’s senior advisor for the Able Americans Project. Melissa identifies as a “happy warrior” and is enthusiastic about driving a dialogue between people living with disabilities or chronic illness and policy-makers across the political spectrum, especially conservatives.