09 Mar 2023 Scott Shepard: Chips Subsidies Will Fail As Moon Shots and Covid Vaccines Already Have

Really, that headline is too long. “Industrial policy will fail,” would have been enough. It’s exhausting that we collectively have to learn this again and again. Industrial policy does not work because it relies on central planning by government “experts,” with all of their ulterior motives, instead of real market-segment experts motivated by the clean, bracing motive of making something cheap and effective so as to make a nice big profit.

A recent Wall Street Journal article’s headline fell even further from the brevity-and-accuracy mark. Titled “Past U.S. Industrial Policy Offers Lessons, Risks for Chips Program,” the piece did as promised: retail some of the problems that face the “chips program” of providing federal subsidies intended to reinvigorate the U.S. microchip industry.

The article tripped at the first hurdle, though, with its subhead: “From moonshots to vaccines, Washington’s efforts to boost specific industries work best with focused goals.”

No, they don’t. Focused goals don’t help to make industrial policy successful, whether it’s cooked up in Washington, London or Paris, or in East Berlin, Moscow or Beijing.

Consider the two examples that the story focuses on as examples of industrial-policy wins. Neither of them were in any way natural developments in normal, competitive industries, and so provide no support for the idea that industrial policy can be successful.

The U.S. space program, and particularly the Apollo program, which arose in answer to the call “that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to Earth,” was about as far from normal industrial development as anything could be.

It wasn’t at all about fulfilling a market need and wasn’t really even about being on the moon. You can tell this because, having achieved the goal before 1970, the politicians and the public both recognized that there really wasn’t yet much to do up there, and so we stopped going. It’s been more than half a century now, and we haven’t sent anyone back up.

When manned flight to the moon resumes, it will very likely be the result of private, market activity – activity undertaken because there is some market value to being on the moon, and thus won’t prove a one (or half-dozen) off, but will grow into an industry (unless government interferes).

Rather, as Americans over- and mislearned the lessons of Sputnik, and took Advise and Consent a bit too much to heart, the moonshot arose as part of the Cold War against the Soviets. In that sense, it was much more like the Manhattan Project than any sort of regular industrial development. In war, governments will spend absolutely stupendous amounts of money – amounts that could never make any sense in a competitive market context – to challenge their adversaries. And in pursuing their goals, they are by definition only competing against other government operations.

Because of the tremendous sums involved and the market-inutility of going to the moon in the 1960s, the U.S. government wasn’t competing against anyone except the Soviet government, so the operation didn’t have to be tight or honed or economical – it just had to be better run than the five-year-plan/no-competitive-inputs version that the Soviets were running. It would have been a hell of a thing if we had somehow lost to that.

Likewise, the recent vaccine developments are nothing on which to model, or to sell as a success of, industrial policy. Most importantly, the vaccines failed, as vaccines. Up until 5 minutes ago, vaccines were understood as products intended to keep you from getting whatever you’re being vaccinated against. These didn’t, despite being subsidized and mandated on that premise.

They’re also turning out potentially to have a lot of terrible side effects, and may prove to have been more dangerous and damaging to younger people than the covid virus was ever going to be. But for liability waivers, those vaccines probably would bankrupt their manufacturers (and may still if, as seems increasingly likely, Pfizer in particular knowingly withheld safety and efficacy information from the public and stopped vital trials and tests because they suspected they’d get bad results. I can’t imagine that those liability waivers cover willful coverups and reckless disregard of suspected risks.).

So the vaccine product was bad, despite being funded with, again, normally incomprehensible amounts of federal money. It was produced quickly, but that wasn’t the result of government industrial policy or even government money. The speed at which it was created arose from the government waiving all sorts of stultifying regulations, the sorts of regulations that make everything these days take far, far longer than it otherwise would need to, without adding much benefit to the public.

Now let me anticipate an objection. Wait, I hear some critic shout, “You just said that the vaccines weren’t very good, and then praised stripping away regulations. Isn’t it the regulations that keep bad products from getting out to the public?” No, regulations aren’t necessary for that. What’s necessary to keep from the public products that a company knows or suspects will be unduly dangerous is the common-law tort liability for negligent and willful behavior that the government waived for Pfizer and the other “vaccine” developers. If companies know they’ll be held liable for their culpable misdeeds, they will avoid those misdeeds and the public will get all the caution that’s appropriate. Under “safety” regulation, we get all the delay that government officials think useful, which very often has nothing much to do with genuine safety at all, and never, never cares for efficiency.

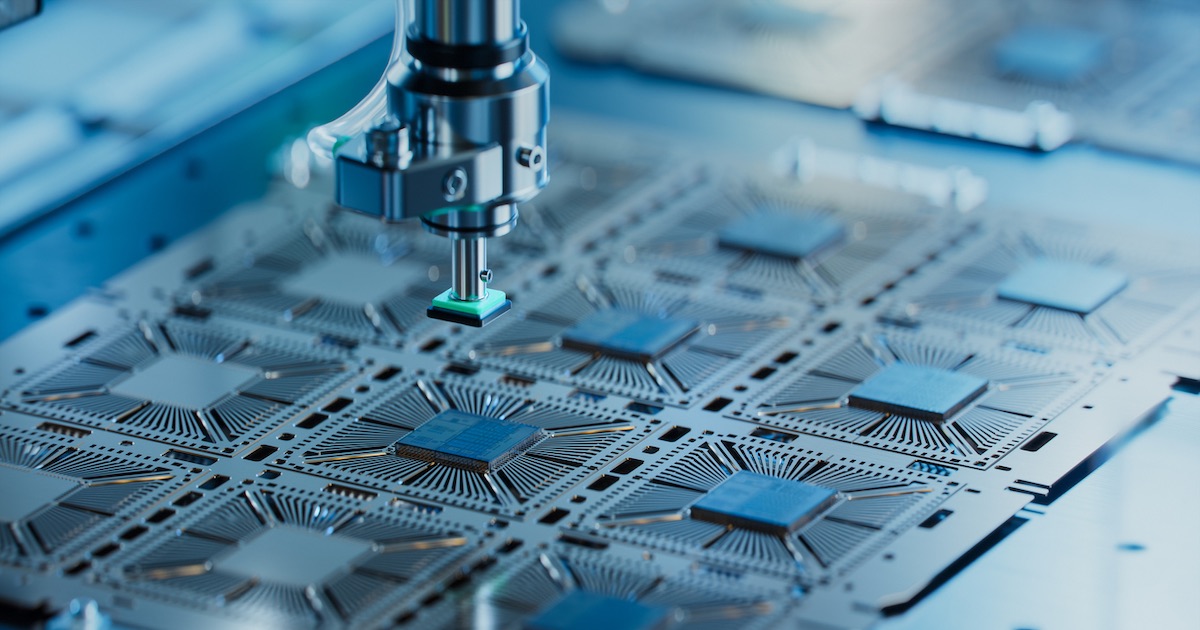

The Apollo missions and the covid “vaccines,” then, provide examples that are just about as irrelevant to the manufacture of computer chips as can be imagined. The market for those chips is already competitive, and innovation in that arena proceeds very quickly and very cheaply – hence the long efficacy of Moore’s Law. As a result, the one thing that governments have to offer – great bails of other people’s money – won’t make a meaningful difference.

And as the Journal article illustrates, this Chips program comes without the one advantage the government could offer: diminution of pointless regulation and costly constraints. Rather, the money in the program comes with all sorts of strings that will serve as ropes to tie down any genuine entrepreneurs who might try to use it, strings such as union-worker and DEI-discrimination requirements.

The program, then, like all industrial-policy programs, will be worthless to true innovators, and either worthless or counterproductive in any effort to “bring microchip fabs home.” What it will successfully produce is cash in the pockets of grifters and union workers and other groups this administration prefers. Solyndras as far as they eye can see. Whole crops of giant Solyndra factories for the 2020s, producing massive piles of tiny bits of Solyndra.

They’ll have about as much appeal on the market as the East German Trabant did in the west.

All of this analysis, by the way, applies with the same resonance to the “public-private” regulations that the likes of Larry Fink and Brian Moynihan are trying to foist on American industry. The tort laws would hammer any American company that provably contributed to real harms as a result of their carbon output, for instance, without the need of any dictates from the likes of them. But for reasons that have been well rehearsed in these pages, such a thing is not provable in any way, because it’s not true – which is why left-wing activists like Moynihan and Fink are trying the ESG end-run.

Industrial policy is stupid and results in failure at best and Chernobyl at worst, as Mrs. Thatcher, Mr. Reagan (and even, in his own way, Mr. Carter) came to realize and act upon at the end of the ‘70s and into the ‘80s in ways that saved western economies. If American schools taught real history instead of 1619-style fever dreams, everyone would remember that.

Scott Shepard is a fellow at the National Center for Public Policy Research and Director of its Free Enterprise Project. This first appeared at RealClearMarkets.